‘Anthropology, by Design’

I’ve got this flask that often draws a lot of flak.

It’s just a double-walled stainless steel flask, which I love because it keeps water ice-cold just about all day long. And in a place as hot for most of the year as Pondicherry, for a person like me who needs cold water to quench thirst, this matters.

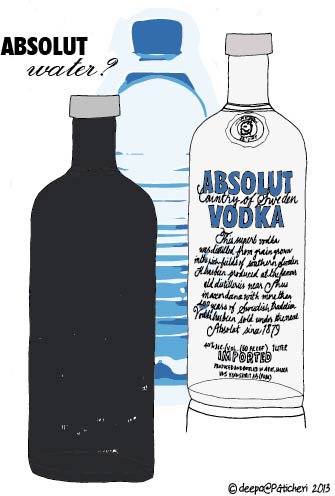

Trouble is, the clean lines and shape of my innocuous flask make it look like it really must carry alcohol. To boot, its matte-black finish only makes the association stronger. Those who know their brands recall Absolut Vodka. Each sip of heat-battling thirst-quenching water instantly becomes—well, a swig. So, when I (Indian, woman, professional) carry it around, there are two responses: those who know me joke about what’s in it, or snigger. Those that don’t, I presume by extension, wonder about my habits and my respectability.

My flask presents one very simple example of how some form of ethnographic inquiry can help to avert design disasters, which can have pretty large consequences for companies. There are innumerable other examples, of washing machine companies which did not account for the range of fabrics that would be stuffed into their drums and therefore produced sari-shredding designs, of goods that teetered on the brink of failure because nobody had bothered to ask whether Indians drink cold things in the mornings with breakfast or even at all.

So the avoidance of cultural faux-pas and design disasters is certainly one level on which anthropological knowledge can have a pretty direct bearing on the product design and marketing process.

But is that all?

Sure, those of us invested in the use of ethnographic methods pull out these sorts of examples routinely, as quick reminders of the relevance of anthropological insight to business process, but I always want to ask, as an anthropologist and researcher: “How to effectively negotiate cultural differences and avert design disasters”--that’s all anthropology has to offer?

I’d like to think that there’s much more to the story than just that. I’d like to think that anthropology—and I use the word deliberately in place of “ethnography,” for the latter’s huge popularity as a people-studying tool also dilutes it considerably—in conversation with design, can not only ask more complex questions about people and their needs, can not only generate meaningful ideas for product development, but can also push these very processes to address more enduring human issues: democracy, access, health, empowerment, rights, social justice, the pursuit of happiness.

Think of it. The positioning of the “user” as focal point has transformed both the ways in which designers go about the business of innovation, but equally how anthropologists relate their work to real-world application. We now collectively think through the design implications of knowing how patients occupy their hospital rooms, how bicyclists cross intersections, or how women in some communities organize their kitchens as fundamentally holy spaces. Understanding the needs of type II Diabetes patients can generate data on designing blood glucose monitors that regulate or modulate user behaviors.

But is it possible to use these advances as springboards to address Big Picture questions—with value beyond business and to social development, governance, empowerment and more?

We have to push innovation in order to connect the dots, making the work we do for bread and butter more meaningful, ethical, and transformative. This is my agenda in this series of posts on ICE. How do we use objects in our daily lives—what is our “material culture”? How does knowing that create spaces for educational and technological intervention? Where are the opportunities to use new technologies to argue for the value of anthropology—not just in negotiating cultural difference, but in rethinking ethics, social justice, and responsibility? How might anthropology and design work together to address these multiple goals?

I’ll close with a quick example. I recently came across this image of “post-colonial” tea bags, produced by a student Samantha Perkins, for a design project investigating post- colonial discourses using, not coincidentally, tea.

Here categories from social theory are inspiring design, and a designer responds with a much-needed visualization of social theory. From this conversation can emerge not simply a reflection on post-colonial theory via a design project, but quite simply a new experience of (identi-)tea.

The categories invite reflection: is it any more possible to idly infuse hot water with a teabag labeled “marginality” or “surveillance”? What would happen to “teatime” if you were really compelled to take stock of commodity, labor, and political histories? Perhaps indeed this is one way in which esoteric theoretical constructs can be translated such that they infuse (pun fully intended) daily practice?

I hope you’ll join the banter as I pour those sorts of questions into my dubiously shaped bottle, and serve them neat on ICE, a little at a time.